One of the stars of Warbirds Over Wanaka International Airshow 2024 was North American P-51D Mustang NZ2423, owned by The Biggin Hill Trust and flown from Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Base Ohakea. A few weeks before the aircraft’s airshow debut at Wanaka Vintage Aviation News sat down with Trust chairman Brendon Deere to hear the story of how, after decades in a farm shed, this Mustang was restored to as-new condition.

By Zac Yates

On November 11th, 2023 P-51D s/n 45-11513 flew for the first time after restoration; 66 years, five months, and twelve days after making the final flight of the type in RNZAF service, where it wore the serial NZ2423. As related in our story late last year the aircraft, now bearing the civil registration ZK-BHT and the radio callsign of Mustang Two Three, had been saved from the scrapman, briefly looked at as the source of parts for a hydroplane, and then stashed in enthusiast John Reginald Smith’s farm shed of aviation treasures for more than fifty years.

In his lifetime John Smith had countless enthusiasts call to his farm near Mapua, at the top of New Zealand’s South Island, in the hope of seeing his remarkable collection of aircraft which included the Mustang, a de Havilland Mosquito, a pair of Curtiss P-40s, a Lockheed Hudson and many others. Brendon Deere was one of those enthusiasts. “I’d seen it probably 40 years ago, when it was still in John’s shed,” Deere told us. “Because the Mosquito [was] the prime attraction, most people probably never saw the Mustang. I’m sure when I first saw it, it was somewhere else in the shed, but I can’t remember.”

Over the years Smith became so inundated with offers to purchase his aircraft that — as legend has it — he was forced to disconnect his telephone line. He would carefully “interview” visitors when they arrived to assess whether or not to grant them access to his collection as they were genuine enthusiasts or if they were about to get out their checkbook: this author has been told stories of folks who spent three hours talking airplanes with Smith without ever getting a glimpse inside his famous shed. Others, however, have told of how they were able to pass Smith’s scrutiny, the shed would be unlocked and the excited visitor would be confronted with a building packed with warbirds, Mosquito NZ2336 dominating the view. Some would even be invited to sit in the Mosquito’s cockpit.

When the news broke that Smith had died on August 7th, 2019 the warbird world was immediately abuzz with what would happen to the one-of-a-kind collection. Many Kiwi enthusiasts feared the aircraft — all veterans of service with the RNZAF — would be sold overseas, lost to foreign buyers who could paint them in schemes that ignored each aircraft’s heritage.

Fortunately for the vintage aviation community Smith’s family consulted with local experts to find the right home within New Zealand for each aircraft in the collection: the P-40N NZ3220 Gloria Lyons, Mosquito NZ2336 and Smith’s own de Havilland Tiger Moth ZK-BQB entered the stewardship of the Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre in nearby Blenheim (the Mosquito and Tiger Moth have since been returned to ground-running and taxiing condition respectively); P-40E NZ3043 Bess to a partnership (also at Omaka) where it is under active restoration to airworthiness; North American Harvard NZ1068 to Auckland-based Nick Sheehan (again under restoration to fly); spare parts not needed for the Mosquito (and a second Mosquito identity) went to renowned “Mossie” restorers Avspecs Ltd; within months the collection had been dispersed to worthy new owners across the country.

It was at this point, nearly forty years after their first encounter, that Brendon Deere re-entered the picture. His Biggin Hill Trust had previously restored Supermarine Spitfire Mk.IXc PV270, ZK-SPI to airworthiness (in the colors of the aircraft his uncle Air Commodore Alan Christopher “Al” Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC & Bar flew when he was Wing Commander of RAF Biggin Hill) and operated it on the Kiwi airshow circuit for more than a decade. In 2012 he re-imported the Grumman TBM-3E Avenger BuNo.91110, ZK-TBE which had previously been part of the late Sir Tim Wallis’ Alpine Fighter Collection at Wanaka and repainted it into RNZAF markings as NZ2518, Plonky (the same colors it had worn while in Wallis’ ownership). Initially on his own, and then in conjunction with the Air Force Heritage Flight of New Zealand, Deere’s name soon came up in the Smith family’s discussions.

“When John died and the family started considering what they were going to do, I spoke to Bill Reid [new owner of Smith’s Lockheed Hudson NZ2043],” Deere said. “Bill mentioned that they were potentially interested in a new home for the Mustang, as long as it stayed in New Zealand and somebody was prepared to put it back in the air. So they were the two conditions. And the family — eight of them — came up here to have a look at us and to see what we would be interested in doing; they seemed pretty happy with what we proposed, and that’s how it came about. We were able to purchase the Mustang off them, and the rest is history.”

Once the aircraft had been eased out of its home of more than 50 years and given a clean (the shed was full of dust which forced many working there to don masks to protect their lungs) the airframe was loaded aboard a truck and trailer while several tons of parts were gathered from all around Smith’s property and containerized. Deere said the sheer number — and location — of spare parts took the Mustang team by surprise.

“John had stashed stuff all over the place we didn’t quite realize. For example in the gun camera compartment, and on top of the clamshell doors. When we first inspected the aircraft, there were bits in the engine bay that had been shoved under the cowls. And we were to get some surprises later as well. When we got the aircraft, a lot of the pipes weren’t there. So we’d factored in replacing those, but one of the crates that we got from John was full of pipes: every pipe for the aircraft except one. There was a lot of stuff that came with the Mustang that’s been particularly useful, or that we’ve been able to make use of in other ways.

“There were a couple of complex panels at the back missing which we got from the U.S. I don’t think there was anything missing, to be honest [other than] little trim things — I suppose they’re decorative things — but the pilot’s relief tube was missing. We put that back in, not that it’ll ever be used! But fundamentally it was complete. And I think that’s the thing about it: when he got it, it was still pretty complete. And when we got it, it was unchanged. John had been pretty careful about letting people get too close to it.”

Possibly the biggest issue facing the restoration was the wings, which had been gas-axed outboard of the main landing gear so they could be taken by truck — three at a time — to the ANSA company at Nelson, several miles from the Mustangs’ storage depot at RNZAF Woodbourne, near Blenheim.

Deere takes up the story: “I understand one of the plans for the aircraft was to use them as orchard wind machines, but they didn’t factor in the cost of running them: it would have been horrendous. So that’s part of the reason they could leave them on their wheels, tow them around to orchards and get rid of the frost.

“So fundamentally, we had an aircraft where the wings had been chopped off. But the Mustang is quite a simple wing compared to something like the P-40, or certainly compared to the Spitfire, in that it’s only got two spars. They’re both just folded aluminum: there’s nothing special about them. And of those two spars, each of them is divided into two parts, so in fact, what they’ve done is cut through the inner spars. We’ve replaced all the spars, for obvious reasons.”

While the restoration of the Spitfire airframe had been done entirely in-house by Deere’s team it was decided to send the mainplanes to Odegaard Wings in Kindred, ND for restoration, a decision made based on several factors.

“One key part of it was project timeline. Doing the wings ourselves, as we’d never done them before, would have added another two years to the project. And I decided I didn’t want another five-year project. So I made the decision that we would be better off to send them off to somebody that’s already got the jigs, already got the know-how, and had a really good reputation for what they do.

“So Odegaard’s been a simple choice for me, even though they were miles away. That decision was made fairly early on, and it was just a matter of shipping everything to them. They were quite interested in the job because they do a lot of new-build wings, but they don’t do as many original aircraft restorations. So that was something of interest to them. And they had a slot that one of their jigs was coming free, so it was just good timing.

“Most of it’s original. You inevitably reskin, because those are stressed-skin aircraft. But I don’t think any of the wing frames were changed; all the gun-based stuff’s original. Most of the complex areas they could just reuse and they were able to refurbish. So the end count on new stuff was largely limited to wing spars and a couple of specialist areas like the gun ports, which are complex: they had been damaged in the cutting, so we had to replace those. But the wings are pretty original, bearing in mind the wings are a composite anyway, from two aircraft: the other wings that John had were off NZ2417 which is the Mustang that went to Kermit Weeks, which has got another aircraft’s [NZ2409] wings on it.”

Another simple decision was where to send the aircraft’s Packard Merlin — the same engine NZ2423 left the Grand Prairie factory with in July 1945 — for overhaul. While New Zealand is renowned for airframe restoration there are few specialist engine shops so the Merlin was boxed up and airfreighted (due to time considerations) to Jose Flores’ team at Vintage V12’s in Tehachapi, CA.

“Jose said it’s one of the best they’ve ever seen. The stuff that needed to be replaced was pretty minor. And it was half-life. It’s probably the newest engine they’ve ever seen. And certainly was one of the cleanest: I think Jose said it was one of the cleanest they’ve ever seen, because it was all inhibited. So at the end of the day, it’s back to effectively zero time. But it still was pretty new anyway.

“[The Merlin]’s never been touched, as best as we can tell. It spent a bit of time outside at Ruffell’s but it didn’t show any signs of degradation or anything from that. And when we took cam covers off, it was in beautiful condition. So as you would expect, it’s half-life. So it was a straightforward job for them. And once we got the engine back, we were able to mount it and plumb it and all that good stuff.”

The propeller was overhauled by while Maxwell Aircraft Service in Minneapolis, MN and six replica .50cal Browning machineguns were produced by Aero Trader at Chino, CA. Back at Ohakea, although Mustang Two Three’s fuselage was remarkably original and complete that didn’t mean there weren’t issues for the Biggin Hill team to rectify.

“A simple example is the fuselage longerons, which are the extrusions. They had signs of corrosion on the horizontal surfaces as the rats had lived on them. And so you had 60 years of rats peeing on the longerons, so we had to replace those. But Odegaard supply those — they’ve got all the extrusions. And you just say ‘I want these four pieces’ and they ship them to you. But the Mustang structure is so simple that that’s it: that’s really the structure of a Mustang, is those longerons. So once they’re replaced, you’re dealing with a few frames and some very heavy skin.

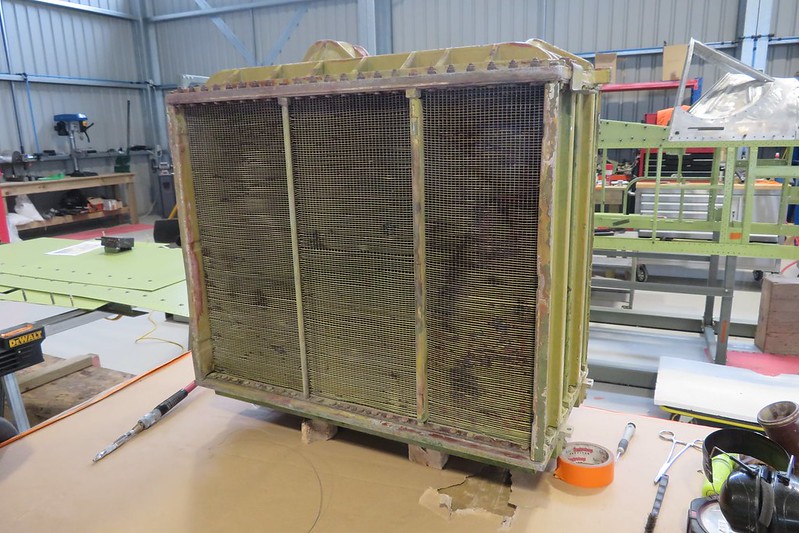

“On the engine mount, there’s four big forgings or castings which hold the lord mounts. Three of them were good, one of them wasn’t. But you can get new ones from Cal Pacific Airmotive in Salinas, California. There was no shortage of sources of new stuff. But we’ve actually had to buy very little. The things that we expected to replace, in many cases some big stuff, we haven’t. The big rubber bladder fuel tanks for example might as well have been brand new: they’d been inhibited by the RNZAF, they’ve been kept in the darkness, and so they were essentially brand new. The radiator, once we cleaned it out, might as well be brand new. So those are big wins.”

According to Deere, who has now “been there and done that”, the differences between the Spitfire and Mustang return-to-flight projects were many and eye-opening.

“The difficulty with an aircraft restoration is you can have the best plan in the world and you’re still going to get surprises. I’ve often said with the Spitfire project we had good weeks and bad weeks. We had good days and bad days. We had good mornings and bad afternoons. Good hours, bad hours. The Spitfire was a perennial nightmare, whereas the Mustang is so much easier. Spitfire stuff is hard to get and hard to find. And I spent a lot of time when I was overseas travelling looking for stuff because Spitfire stuff is quite rare and people want to collect it. So anybody can buy something off a Spitfire on eBay and put it on their mantelpiece, but if you want it for an aeroplane, it’s a different challenge.

“Whereas there’s a huge industry in the US making Mustang stuff. Virtually anything on a Mustang is being made these days. So we had no difficulty getting replacement parts. As you go through the process, you say ‘Well, here’s a part: can we refurbish it back to serviceable?’ or ‘Do we have to repair or replace it?’. So where we came to the decision to replace things we did. It’s really hard to estimate the percentage of original parts. I think it’s around 90%, probably, which is pretty unusual these days.”

For many enthusiasts the issue of the color scheme worn by a restored warbird or other vintage aircraft can be a sore point. Some owners choose to showcase their aircraft as it was when in service, others opt to paint different markings to tell the story of another aircraft. Deere explained that, while he has his feet in both camps with his WWII fighters, in the case of the Mustang there was only one option.

“You could argue with our Spitfire, it’s not painted in its original markings, but it’s painted in something suitable. But with the Mustang there was no question about the color scheme, ever. It was always going to be 2 Squadron [Territorial Air Force]. There’s a lot of Mustangs which are still natural metal, but if you polish an aircraft, you’ve got to keep polishing it. And we’re only 20km (12.4mi) from the sea, and we have a prevailing westerly wind, so we wanted it to have plenty of paint protection. And I think the end result with the High-Speed Silver has come out quite good. In certain lights it looks like natural metal, but it’s doing the job.”

The decision as to who would fly the Mustang was also a simple one. Sean Perrett formerly served in the RAF on the Hawk and Harrier, and flew three seasons with the Red Arrows. Having served 18 years in the RAF Perrett moved to New Zealand in 2003 and joined that nation’s air arm as an instructor and became a founding member of the Black Falcons aerobatic display team.

For several years Squadron Leader Perrett has been the sole pilot for Spitfire PV270 and, to Deere, was the obvious choice to fly NZ2423. “For him, with his skill, it’s a straightforward aircraft,” Deere told us.

“It’s faster than the Spitfire, but not as maneuverable. It’s got a lot more creature comforts, pilot comforts, than the Spitfire has. So far he’s enjoying it. There’s always little things that pop up in a test flying program, but we haven’t had any particularly big issues that we’ve had to deal with.

“Sean’s maximum flight time we’ve had so far [as of January 2024] is just over an hour, perhaps an hour and a quarter. It’s doing everything it should: all the temperatures and so on. The cooling system, we’ve got that in our rig so that’s spot on. The Mustang system is quite automatic, but you’ve got to get the [radiator] door adjustments right to make it automatic. So we’ve had coolant adjustments, oil coolant adjustments. Just mainly those flaps that come down. They’ve got to be set in the right position to make sure that they keep there. And the oil and coolant temperatures are now rock steady. They don’t change. So that’s all set up and running.”

What may surprise many readers is that this better-than-new restoration with meticulous attention to detail is the result of a very small but dedicated team of experienced engineers focused on one aircraft, rather than being the product of a major workshop that has several projects underway at any time.

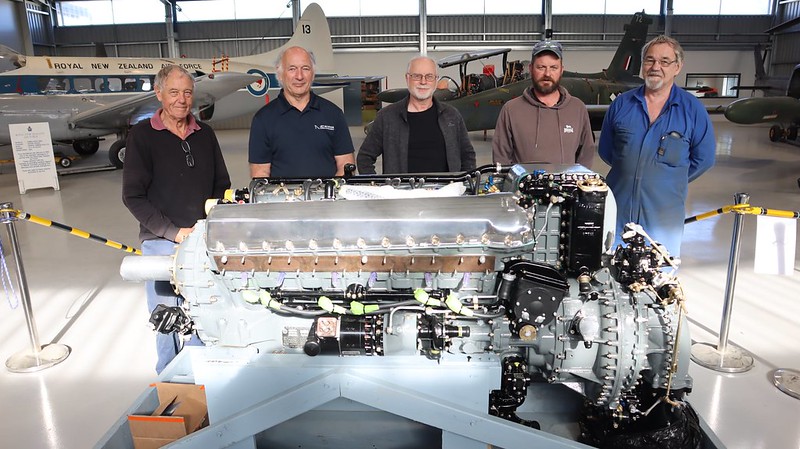

“We’ve had three full-time on the project: Pete Burgess, who is the project leader; Brian Harris; and Joe Deere [Brendon’s son] that worked continuously through it. We also had Jim Garner from Airbus working part time on it, and we also had David Thayer from Whanganui who did the bulk of the wiring and avionics work. So that’s the basic team of five.

![Core members of the team that made it happen: Pete Burgess, Sean Perrett, Brian Harris and Joe Deere. Not pictured is Brendon Deere, who was behind the camera. [Photo via The Biggin Hill Trust]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/NZ2423-team-1024x575.jpg)

“With the Spitfire, we had up to eight or nine people on at any one time: the Mustang’s a much simpler aeroplane. My role was administration: you can’t have engineers running around trying to find stuff so I would do that. It was the first time they’d ever done a Mustang, but for most of them it was the first time they’d ever done a Spitfire. Either you do it or you don’t.”